Telling time is no simple feat, especially in a new language. Different cultures can measure and think of time really differently, so when you study a language, you might end up learning new ways to read the clock, divide up the day, and describe when things are happening!

For example, if you know Spanish, you know that ahorita means… wait, actually, what does ahorita mean? The word itself is the diminutive (small, also used to express affection) form of ahora (now), and in practice it can mean anything from “Yes, omg, I’m on my way!” to “Yeah, yeah, I’ll get to it when I get to it, don’t rush me” to “Oh, I’m definitely not doing that, but I’ll say politely that I’ll do it later.”

Here are more tidbits about how to talk about time around the world!

How telling time varies around the world

In most of the world, the amount of daylight changes with the season. The ancient Egyptians originally divided daytime into 10 equal parts, plus dawn and dusk. At night, they used 36 decans (star groups) to track time, with divisions that shifted seasonally. Later, they transitioned to a 12-hour day and 12-hour night system, which influenced Greek and Roman timekeeping.

In ancient Rome, daylight was split into 12 equal parts, called horae (hours) in Latin. Since there is more daylight in Rome in summer than winter, one summer hour lasted longer than a winter hour! Nighttime was divided into four vigiliae (watches), used mainly by soldiers and night guards.

In traditional Chinese timekeeping, a 24-hour day was divided into 12 “double hours” (called 时辰 shí chén in Mandarin Chinese), with each lasting two modern hours. Each double hour was associated with one of the 12 Chinese zodiac animals, beginning with the Rat (11 p.m. – 1 a.m.), Ox (1 a.m. – 3 a.m.), Tiger (3 a.m. – 5 a.m.), and so on. This system was widely used during imperial China and was essential for scheduling activities, religious ceremonies, and governance. Time was measured using water clocks (clepsydrae) and sundials, which were carefully maintained in royal courts and observatories to ensure accurate timekeeping.

In India, 24-hour cycles were historically split into eight parts, called प्रहर prahara. Another, more precise time-keeping system divided the day into 60 equal parts. Each part lasted 24 minutes and was called घटिका ghatika. Two ghatikas combined made one मुहूर्त muhurta (48 minutes). India also had water clocks (घटिका यन्त्र ghatika yantra) long before mechanical clocks were invented in the West, with detailed descriptions appearing in texts as early as the 5th century CE. In fact, timekeeping was so vital that the Arthashastra (4th century BCE to 3rd century CE) listed it as an official duty of the King and the State.

In Thailand, time is traditionally divided into four six-hour periods rather than the standard two 12-hour periods. The names of these periods are believed to be influenced by the sounds of a bell (โมง “moong” used for daytime hours) and a drum (ทุ่ม “thum” used for nighttime hours) that were used to mark time, though historical records don’t definitely confirm this onomatopeic connection. Additionally, special terms exist for the final (sixth) hour of each period… kind of like noon for 12 p.m. and midnight for 12 a.m. in English! While this older system is still used in casual speech, official timekeeping in Thailand follows the 12-hour or 24-hour system.

In Swahili-speaking regions, such as Tanzania, Kenya and Zanzibar, timekeeping follows a system that is based on the rising and setting of the sun, rather than the midnight-to-midnight cycle used in Western timekeeping. And since Swahili developed near the Equator, those times are consistent throughout the year! Each day, the Swahili clock resets to 0 at what the midnight-based system calls 6 a.m.. This means the day starts at 0, around sunrise—so people in Kenya traditionally count the daylight hours 0 to 12 (what people in a midnight-based system call 6 a.m. to 6 p.m.). And—you guessed it!—what people in Kenya traditionally call 0 to 12 in the nighttime corresponds to 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. in the midnight-based system.

Here are some examples of Swahili times and their midnight-based equivalent:

| Swahili time | Midnight-based time |

|---|---|

| ☀️ saa 1 asubuhi | 7:00 a.m. |

| ☀️ saa 5 asubuhi | 11:00 a.m. |

| ☀️ saa 9 mchana | 3:00 p.m. |

| 🌆 saa 12 jioni | 6:00 p.m. |

| 🌙 saa 1 usiku | 7:00 p.m. |

| 🌙 saa 4 usiku | 10:00 p.m. |

| 🌙 saa 8 usiku | 2:00 a.m. |

| 🌅 saa 12 alfajiri | 6:00 a.m. |

Did you notice the words asubuhi, mchana, jioni, usiku, and alfajiri in Swahili? Those refer to different parts of the day: morning, afternoon, evening, night, and dawn. The words mchana, jioni and usiku are of Bantu origin, while the other two are of Arabic origin: asubuhi from الصباح (aS-SabaaH, “morning”) and alfajiri from الفجر (al-fajr, “dawn”).

This timekeeping system is also used in Ethiopia, and was traditionally used in other places like Sudan and Madagascar as well—places where daylight varies more than it does around the Equator!

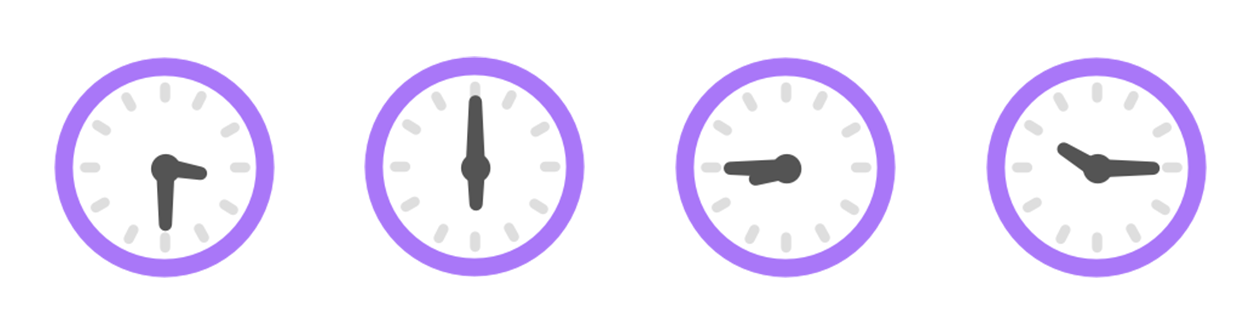

What time is it?

Outside of the U.S., it’s quite common to use the 24-hour clock (“military time”), especially in more formal contexts. This format makes it really clear exactly when something happened: If your flight leaves at 18:00, it’s definitely an afternoon flight, whereas, in the U.S., a flight at 6:00 needs the extra clarification of “a.m.” or “p.m.”

In many cultures and languages, you tell time by focusing on the next hour—the one that is approaching. For example, in Russian, instead of saying one-twenty for 1:20, you say twenty minutes of the second hour—as in, we’re twenty minutes on our way to 2:00. This also happens in other languages like Spanish, French, Italian, and Arabic, but only when it’s closer to the next hour. In these languages, 1:20 is one and twenty but 1:40 is two minus twenty (or two minus a third in Arabic).

Dividing up the day

Personal preference matters for dividing up the day (like those early birds that eat lunch at 11 a.m.), but cultural tradition plays an even bigger role, and you might see differences in the new language you're learning.

Some of the biggest differences you’ll encounter have to do with when the morning begins. For example, in English, we say one in the morning to refer to 1 a.m., but in Russian, ночь (noch’, “night”) is the word you use to refer to the hours a person would (typically) be asleep—so you talk about something happening at one at night instead of one in the morning. This is also true in many other languages like Italian, Turkish, Hindi, and Swahili.

Similarly, different cultures don’t always agree on when afternoon ends and evening begins. In English, 4 p.m. is typically called four in the afternoon, but in languages like Swahili, Hindi, and Japanese, evening is considered to start earlier, so four in the evening is more common.

Spanish doesn’t really have a division between evening and night—instead using afternoon until much later in the day than we do in English—but Spanish has an extra, early-morning period: madrugada. The madrugada occurs after midnight, but before you’d want to wake up. (Unless you enjoy waking up at 4 a.m.) This concept of the early-morning period as a separate part of the day is also found in Korean and Chinese, which use 새벽 (saebyeok) and 凌晨 (língchén) respectively to refer to what Spanish calls madrugada.

Time to see for yourself!

Telling time might be second nature for you in your own language, but that doesn’t mean it’ll work the same in another language! There are lots of differences around the world in how cultures measure time, and learning a new language will put your own language’s time quirks in perspective. Is it time for your next lesson yet? ⏰