In its very early days, Duolingo was built around teaching English speakers languages that were very similar to English–that is, languages that are written in Latin script and have similar written conventions and linguistic properties to English. As we expanded into the wide range of courses we support now, though, we've introduced a wealth of new languages into the app that are increasingly different from English.

The unique properties of each new language mean that, on the engineering side of things, we need to 1) implement new features to help us teach them effectively, and 2) rework some of the logic behind existing features to make sure they work just as well for these new languages as they do for all the others, which sometimes means exploring and correcting assumptions that were made about languages when our code was first written.

Implementing features to improve how we teach

As a software engineering intern at Duolingo, I had the opportunity to help improve our Chinese course. I focused primarily on engineering-side improvements to the course, but some of the work I've done either touches other courses or is readily applicable to a range of other courses. Throughout the process, I got to experience both backend and frontend Android development, and also had lots of opportunities to work with other team members, such as our learning specialists, to get a better sense of how everything at Duolingo comes together to bring quality language education to our learners.

In the rest of this post, I'll give a rundown of some of the specific improvements I've worked on, some of which you may already have started to see in your Duolingo lessons!

More pinyin for learners of Chinese

One of the big things that sets Chinese apart from most other languages is that its writing system is not phonetic. Because of this, both new learners of Chinese and native speakers learning to read Chinese typically learn a phonetic system such as pinyin (拼音) to help learn the pronunciations of characters. While Duolingo does introduce pinyin in the Chinese course when we teach characters, it's still a lot to expect learners to constantly be making the connections between what the characters look like, the sounds they represent, and the meanings they encode.

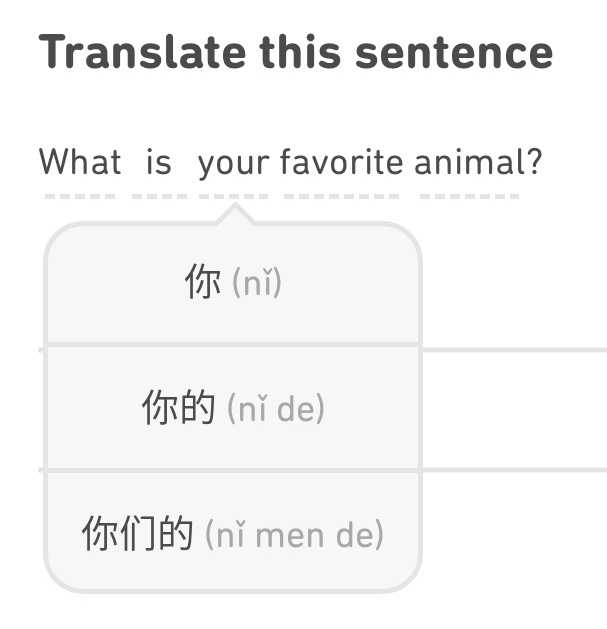

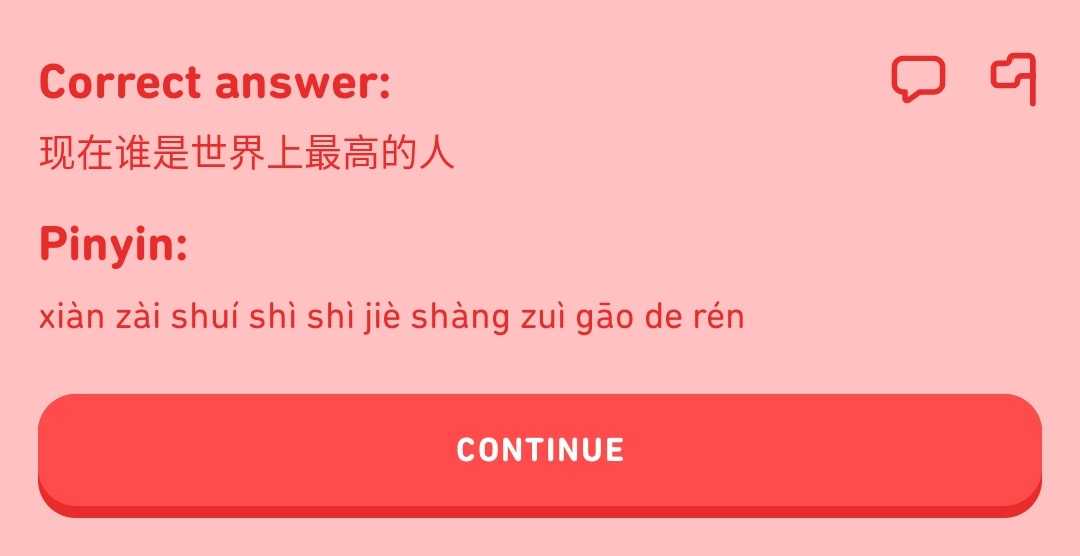

To help teach these things together, we've started showing pinyin in more places in lessons. For example, you'll now see pinyin in hints and in grading ribbons for certain types of exercises on Android.

From a learning perspective, we hope that offering more places where characters can be seen side by side with their pronunciations will better reinforce the connection between them. As we introduce the ability for learners to choose to type in the languages they're learning (more details on that later in this post), knowing pinyin well becomes increasingly important, since one of the most popular ways to type Chinese on a computer or mobile device is using pinyin!

A new way to grade speaking exercises

In many languages, there's a relatively close correspondence between the sounds and the writing system; that is, if you know what a word sounds like, you can probably tell how to write it. English tends to be a little less well-behaved on this front than some languages, in that it has some very different-looking homophone pairs, like "sight" and "cite."

Chinese has an especially high degree of character homophones, which makes it difficult for us to rely on speech recognition to tell us whether a spoken answer is correct. In many cases, a good speech recognition system will be able to guess from context which word with a common pronunciation should be in a given sentence, but in others, it's impossible to tell. Consider the characters 他, 她, and 它: 'he,' 'she,' and 'it.' All three are pronounced 'tā' and because of their similar meanings, context alone won't tell you which one a speaker intended to say.

Off the shelf speech recognition systems may just pick one, but it may not be the one you intended. In these cases your pronunciation was correct, but your answer would be graded as incorrect. That’s not what we want!

To solve this problem, we shifted our grading to be more based on phonetics. Now, if you say 'tā', any character whose pronunciation is close enough will be considered a match, and you will be graded as correct.

In addition, Korean presents a similar challenge, and we employed a similar approach based on more phonetic grading to improve our speaking exercises for Korean learners.

Letting learners switch input modes

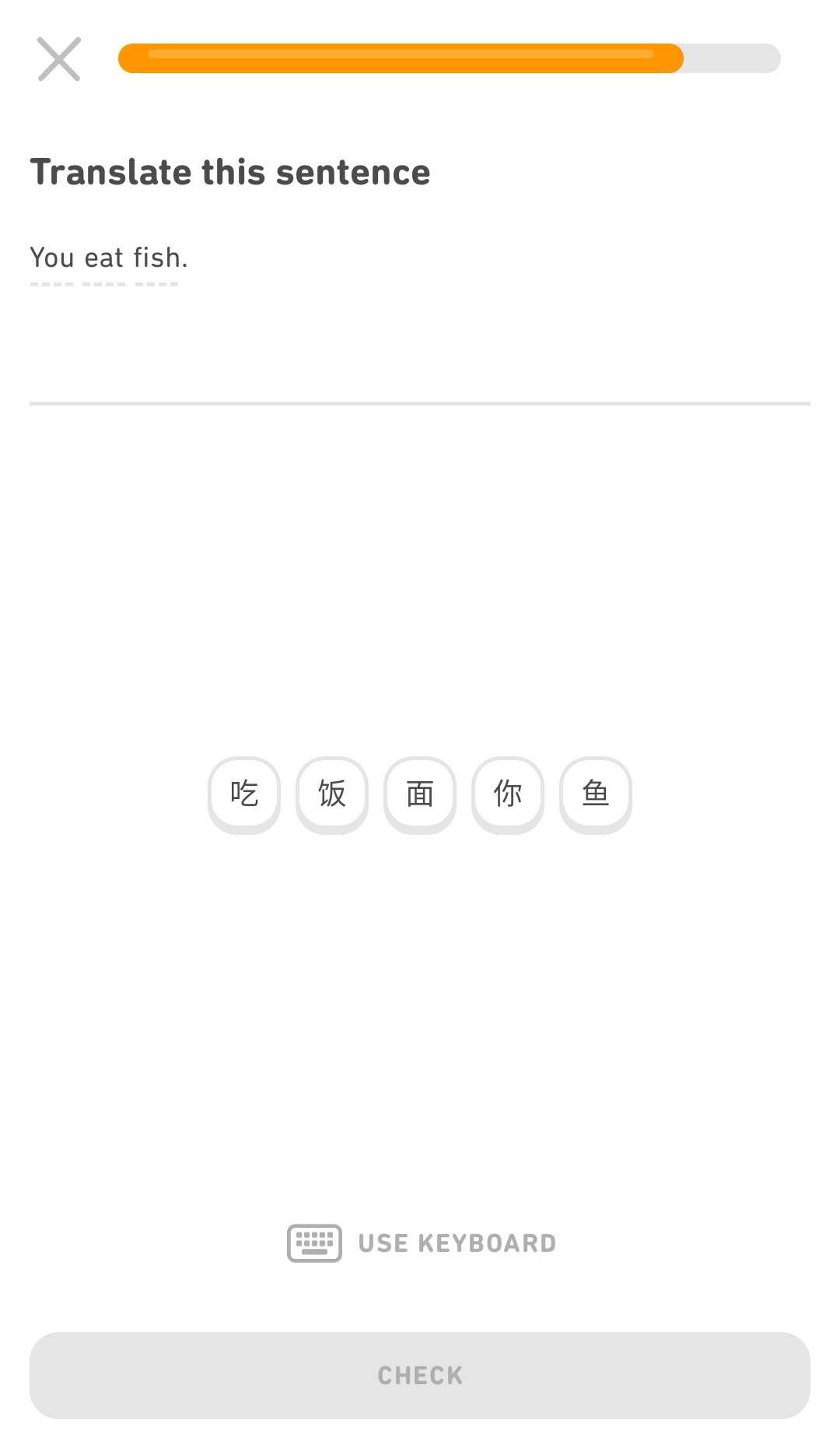

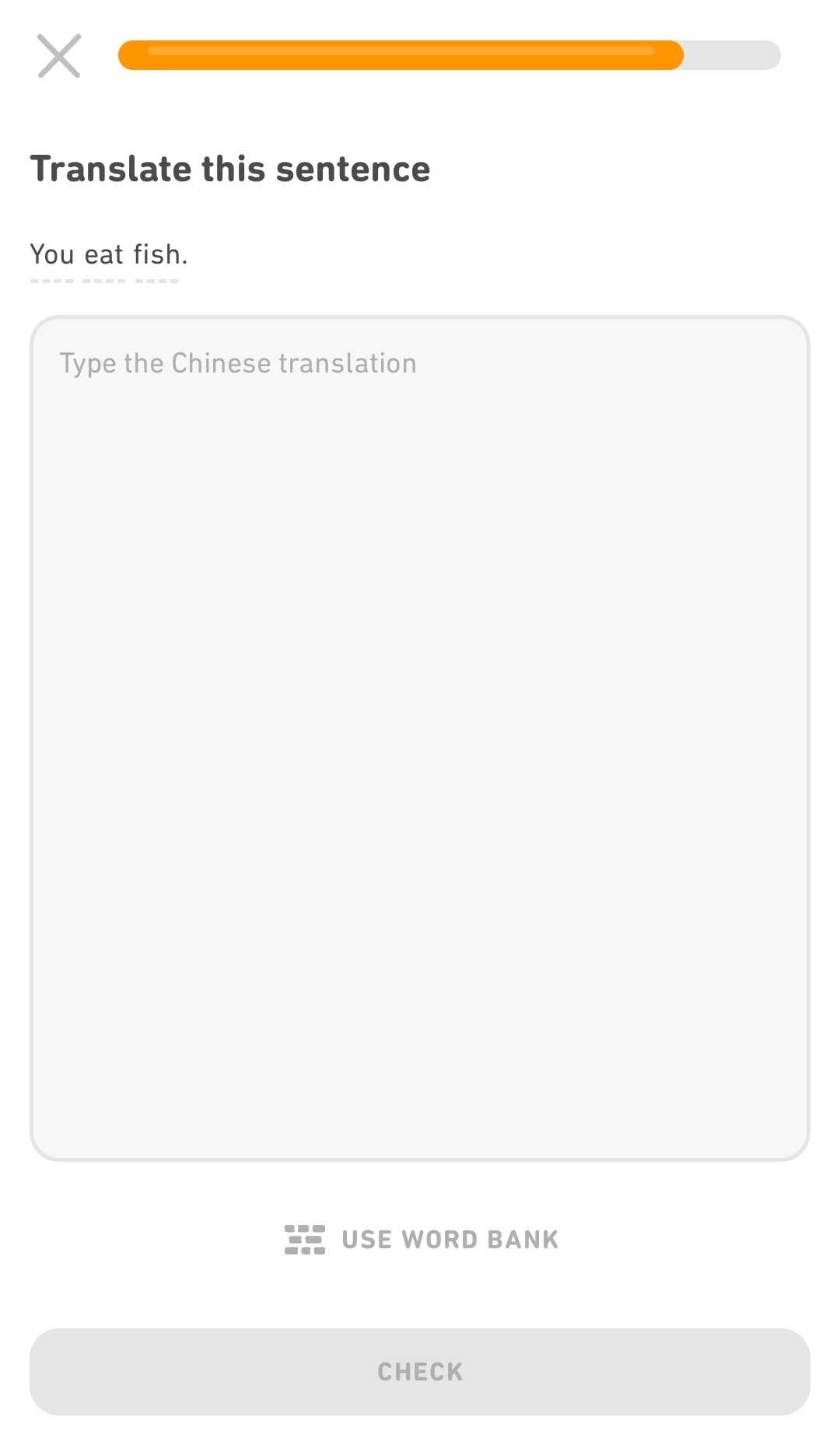

In a number of our courses that teach non-Latin script languages, we only offer translation exercises with a word bank, as opposed to keyboard input. We do this so that learners aren't forced to install, set up, and learn to use a new keyboard or input method for an unfamiliar language. However, we know that answering from a word bank and answering via keyboard input require very different levels of active recall, and it doesn't always feel very challenging to answer from a word bank.

To address this issue while still not forcing anyone to use a completely unfamiliar keyboard, we introduced input mode switching. This allows you to opt-in to using your keyboard instead of the word bank to input answers.

This way, if you're looking for deeper practice in your language learning and you have the ability to install and learn a new input method, you can get that! But if you don't, you can still use the word bank as always to practice your language skills.

Even better, this change isn't exclusive to our non-Latin script languages; the toggle to switch to keyboard is now available in all of our courses (in levels 2 and above), so you can level up your learning no matter what language course you're in!

Rebalancing exercises for character-teaching languages

While testing some of the changes to the Chinese course, I noticed that a lot of the lessons I was doing contained many repetitive "Tap the pairs" exercises.

I learned that the way we distribute exercises of various types in a lesson was optimized for our courses that don’t teach a new writing system, which was the only kind of course we had for a long time. However, this same distribution method tends to result in repetitive exercises in our courses that teach new writing systems. It doesn't make for a very pleasant learning experience to keep seeing the same thing over and over, so for the last part of my internship, I took a step away from Android, where I had been doing most of my work, and jumped into Duolingo's session generator to fix it!

As a result, there is now a simple way to introduce caps to how many exercises of any given type we will generate in a single lesson. With this, we can ensure that no lesson should ever contain more than a certain number of the same kind of exercise, leaving more room for a greater variety of other exercises to help you learn more.

What's next?

A number of the changes I've worked on this summer set the stage for other related changes to happen relatively easily.

For example, the code I've written to surface pinyin in our Chinese course lays the foundation that could open the door for something similar in the Japanese course. In addition, the code that limits the number of character matching exercises we show in a lesson can easily be reused to perform similar tweaks for other types of exercises. This will make it easier for us to fine-tune how exercises are balanced in the future, so we can continue to make Duolingo an even more effective tool for teaching you new languages.

As a heritage speaker of Chinese, a linguistics major, and a person passionate about education, I'm excited about the changes I've helped to implement, as well as for the future improvements that are made possible as a result. We hope you'll look out for them and enjoy this updated learning experience!