How to solve a problem like locking

The Duolingo app is famous for encouraging users to do their lessons. While Duo the owl’s methods vary, the most effective method for reminding users about their learning goals is via notifications. In order to schedule and send hundreds of millions of notifications each day, we use a system known as comeback.

When a user does things like finishing a lesson, we will calculate when we should send them reminders for the following days and store that schedule of reminders as a row in our database (the DB). At the same time, we’re also scanning the database for notifications that are ready to be dispatched and sending them to users across the world! Interactions with a DB, like updating or reading a row, are known as transactions.

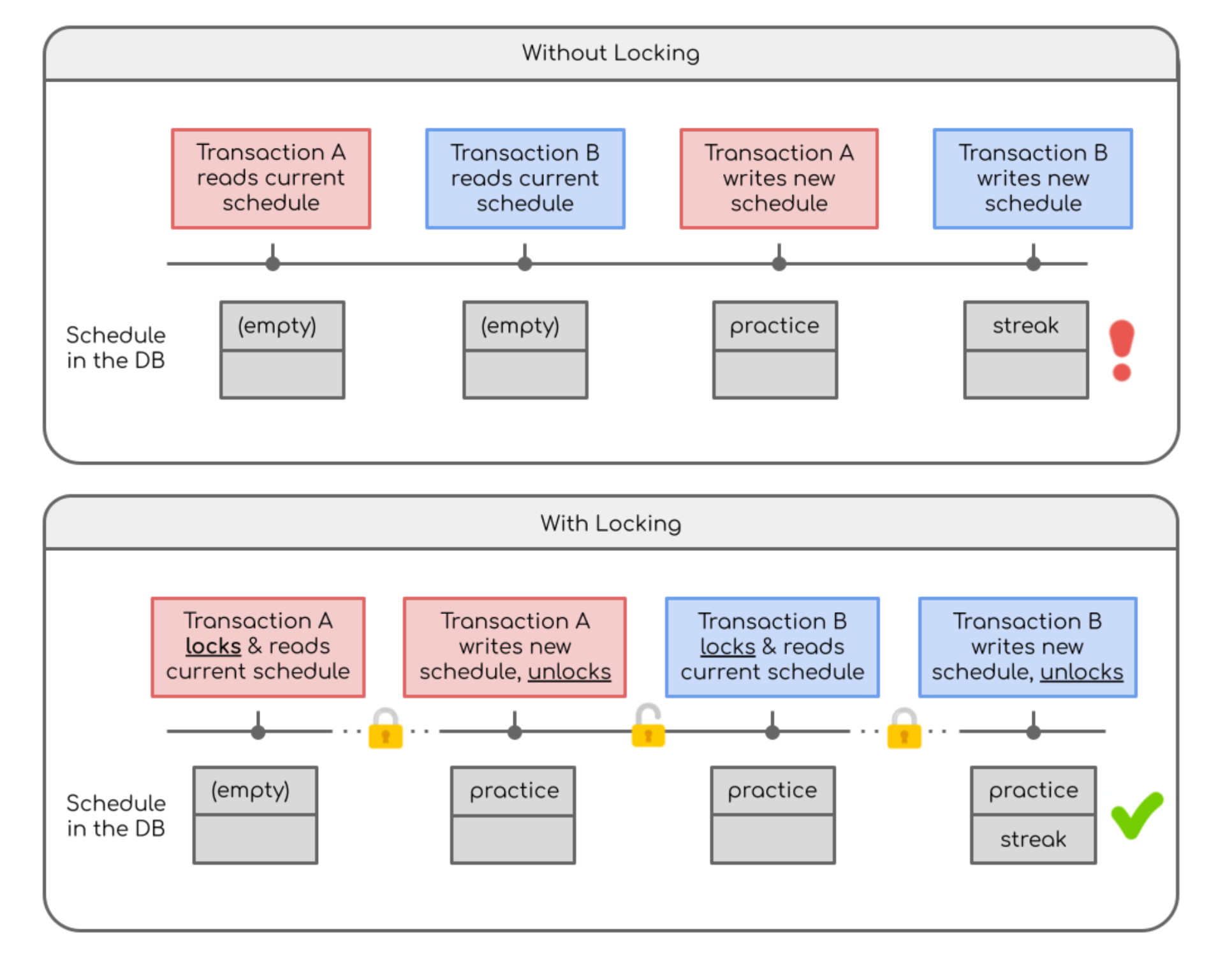

A classic problem with DBs, though, is that you need to make sure that if one transaction is updating a row, nobody else tries to modify it at the same time. Otherwise, reminders could get overwritten if transactions interleave each other. (See more in the appendix below.) So, before writing to the DB, we would lock a specific row so that anybody else trying to touch it had to wait.

Unfortunately, all of this traffic on the DB led to a lot of locks being waited on. And when the DB had to check whether a row was locked and who was holding it, it took some time. As the DB spent more time checking locks, the last time it had to spend on actually updating the rows, leading to delayed notifications. The extra load from lock contention got so bad that notifications could be delayed by more than 20 minutes, and those minutes can be critical if it’s the last reminder to save your streak!

As our user base grew, we started to see this behavior more, especially during peak notification traffic on Saturday at about 10 AM Eastern. Our notifications team would often have to monitor metrics at these times and be ready to intervene if necessary, a practice lovingly referred to as “watching the Saturday morning cartoons.” But this practice was not sustainable, so we looked to address the locking issue at the source.

Taking a look under the hood

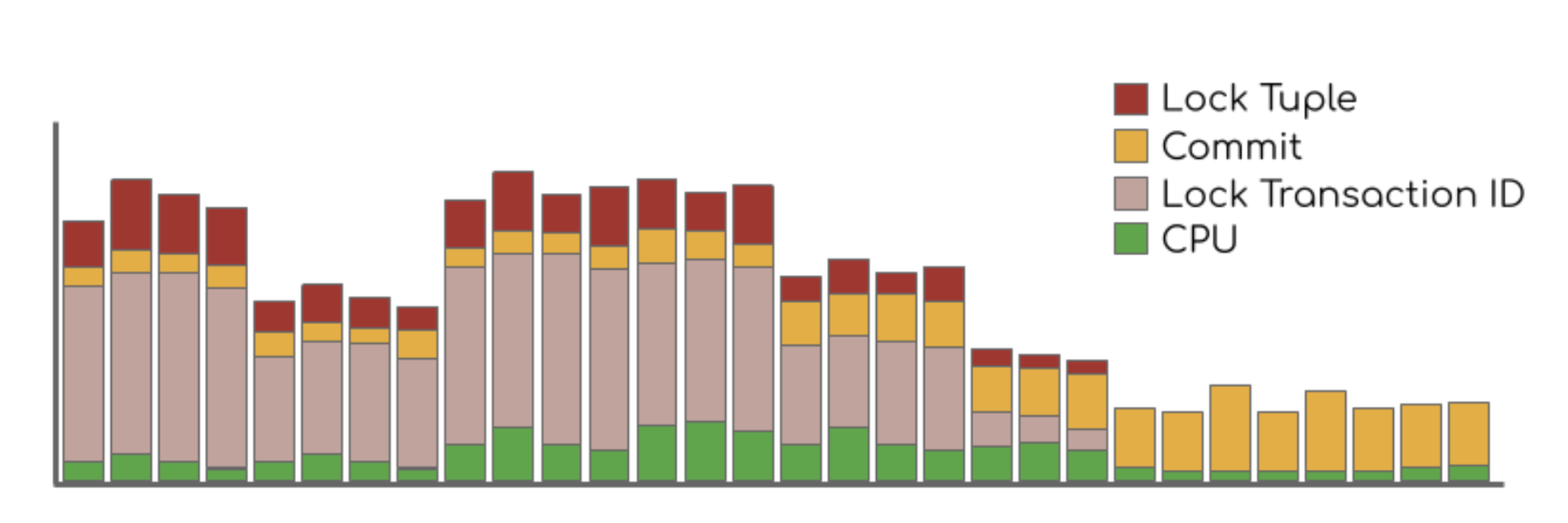

To identify which transactions were holding the locks, we used SQL queries to profile the DB at different amounts of traffic.

What we found was that updating the schedules could take upwards of ten seconds!

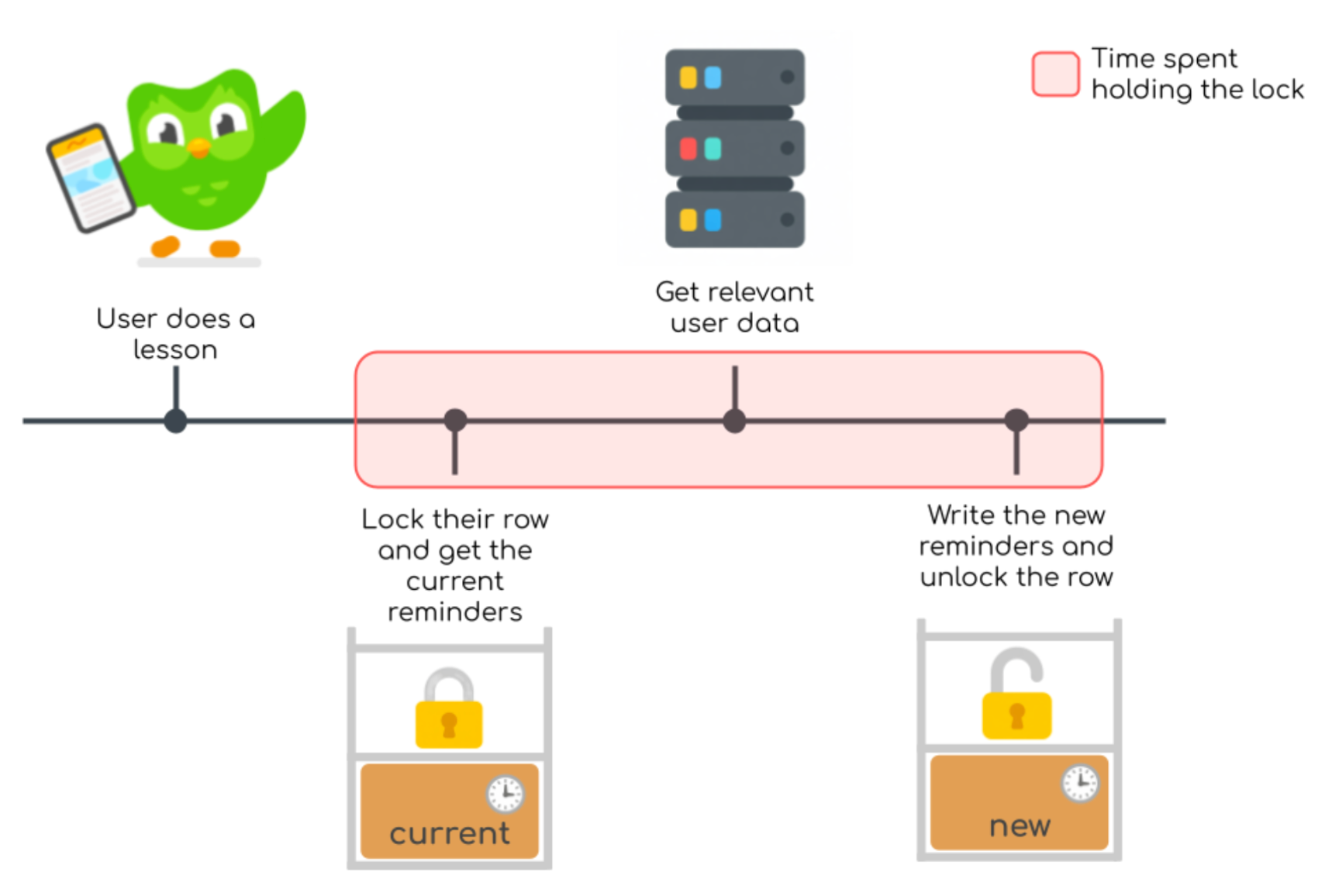

When we updated a schedule, we would first lock the user’s row. We would read the current schedule and add any new reminders based on the user’s current state. Then we’d write back the new schedule and release the lock. And a lot of this time—over half!—was spent making network calls to get a user’s details (like the length of their streak) so that we could schedule the right reminders.

If we could reduce the amount of time each transaction is holding their locks, then there would be less waiting, so the solution would be to do these time-consuming network calls before getting any locks—and finally, this is where optimism comes into play.

The power of positive thinking

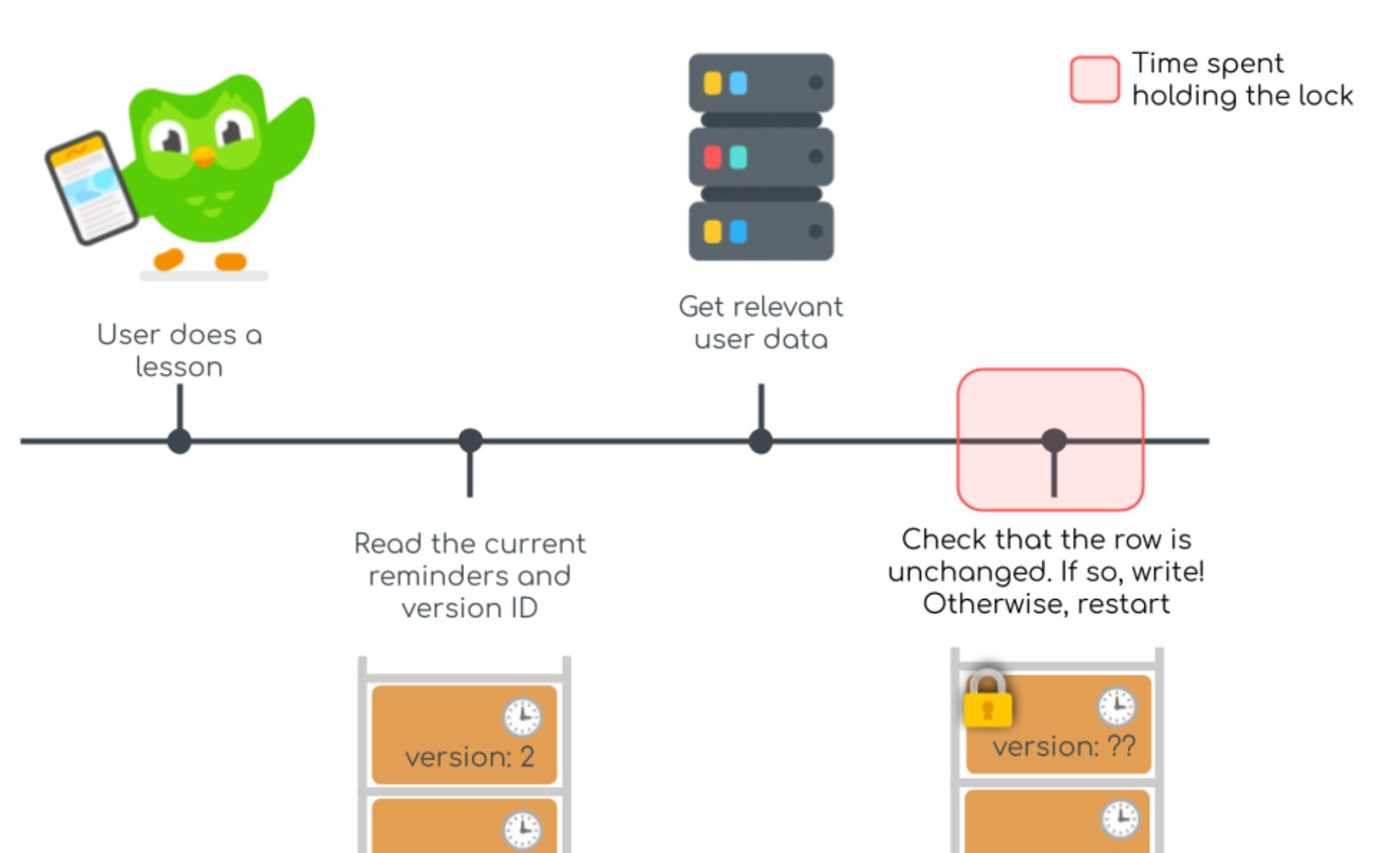

With optimistic locking, we read the current schedule without locking anything! We create the new schedule of reminders, but before we write back, we check if anyone else has updated the row in the meantime. If the row is unchanged, then it’s effectively as if we had locked the row, and so it’s safe to update it with our changes.

But if somebody else has updated the row, then we don’t want to overwrite their work, so we try from the very beginning, reading the now-current schedule and doing it all over again.

To enable checking if the row had been edited, we needed a version ID for each row—basically a number saying “this row is on version 5.” And then each transaction would only commit its changes if the version ID was the same as what we saw at the beginning of the transaction.

One caveat of optimistic locking is this “try again” business. If there are a lot of ongoing transactions, then won’t this cause a lot of this work to be wasted when the transaction has to start over? And the answer is: yes! Fortunately, though, we can check how often this happens and implement improvements to prevent eating too much work. Monitoring this failure mode and others is almost as important as implementing the fix itself.

Test, Monitor, Safeguard

While we felt bullish about this plan, it would be foolhardy to jump right in without testing it first. It’s good to be optimistic, but dangerous to be naive! With service as critical as notifications (see the appendix below), we needed to prove this would work before touching any code.

To test our plan, we created a replica of the DB with simulated mock traffic on it so that we could assess the impacts of the changes. For example, we were able to test adding a new column for the version ID and found that it would take 22 milliseconds, which is well within the acceptable downtime. We also tested various approaches for storing the version ID and checking if it had been updated, allowing us to find the most efficient setup.

We were concerned that a lot of retried transactions could add load to our service, so we added tracking for how a transaction had to be retried because the version ID had been updated before it could write back to the DB. We found this to be a fairly rare occurrence, so we proceeded with the change.

For migrating from the old system to using optimistic locking, we added a feature flag, allowing us to instantly change which part of code is used without having to deploy any changes. This was useful so we could slowly move users over to the new system while checking for errors, but also very handy in case we needed to quickly revert the migration. (Fortunately, that didn’t happen!)

Ending on a High Note

After we switched to optimistic locking, we found that the load on the DB due to locking was reduced to negligible amounts! Without needing to wait on locks, our transactions to update reminders fell from about 16 milliseconds to <1 millisecond!

Good News

- We reduced the amount of resources used for the database, saving over $100k per year!

- We stopped having delayed notification incidents, and we expect the current database setup to handle user traffic growth for several years

Other News (not bad, but good to note)

- Optimistic locking did lead to heightened commit load on the DB since it can’t batch transactions, but overall load is still down and we identified strategies for reducing commit load.

Takeaways

- The main lesson of optimistic locking is to try to limit the scope of locks to only cover work that directly involves the DB.

- Testing every step on a mock DB took extra time, but led to a smooth transition to optimistic locking with only a few seconds of downtime.

- Proactively determining failure modes and adding monitoring in advance made it easy and fast to determine whether the migration was working correctly.

- Most importantly, Saturdays can now once again be spent watching actual cartoons!

Like solving tricky problems with clever, inventive ideas? We’re hiring!

Appendix

Below is an example of interleaved transactions. Say we have transaction A that is supposed to add a practice reminder and transaction B which is supposed to add a streak reminder. Without locks, it’s possible for the transactions to both read an empty schedule, and then the last transaction to write will overwrite the first transaction’s changes!