Hello, learners! It’s Dr. Emilie Zuniga back again on Dear Duolingo. This week’s linguistic puzzle is a bit different from unnecessary words and the hardest languages to learn. It highlights another way languages differ in how they organize ideas and concepts.

That is a question I’ve thought about *a lot* as a linguist and a professional language learner. Prepositions are some of the least predictable parts of any new language, and there’s a good reason for that—they reflect something much deeper than other kinds of words, namely the diverse ways in which different groups of people conceptualize the world around them.

Not all words have a perfect match

When you learn a new language, you can expect to find words for many things that exist in your own language: You’ll learn a way to say street and car, and also words for more abstract things like strength and equality. For these words and concepts, there will often be a clear translation from one language to the next—so if you ask a French speaker how to say equality, they’ll have a simple answer (égalité).

On the other hand, if you ask a French speaker how to say in in French, the answer will be Ça dépend ! (It depends!) That’s because in is a preposition, and prepositions work really differently than nouns like street and equality. They are part of a group of words called function words, which not only are abstract, but also serve a grammatical purpose.

That grammatical purpose may not be essential to communicating basic meanings, but our brains seem to want this kind of nuance—people who use communication systems that lack prepositions, like pidgins, spontaneously create them!

Languages carve up meaning differently

Unlike nouns, adjectives, and most verbs, prepositions need context around them to come to life.

You can probably pretty easily define (and even draw!) street and car—but it’s a bit tougher for the abstract nouns strength and equality, although you could rely on associated images like a flexed bicep or scale of justice. And then… what do you do for prepositions like at or by? 🤔 Even native speakers can’t clearly articulate what their prepositions mean. (And forget about drawing them!)

Instead of representing a straightforward concept, prepositions get to how a community thinks about relationships between space, time, movement, and more.

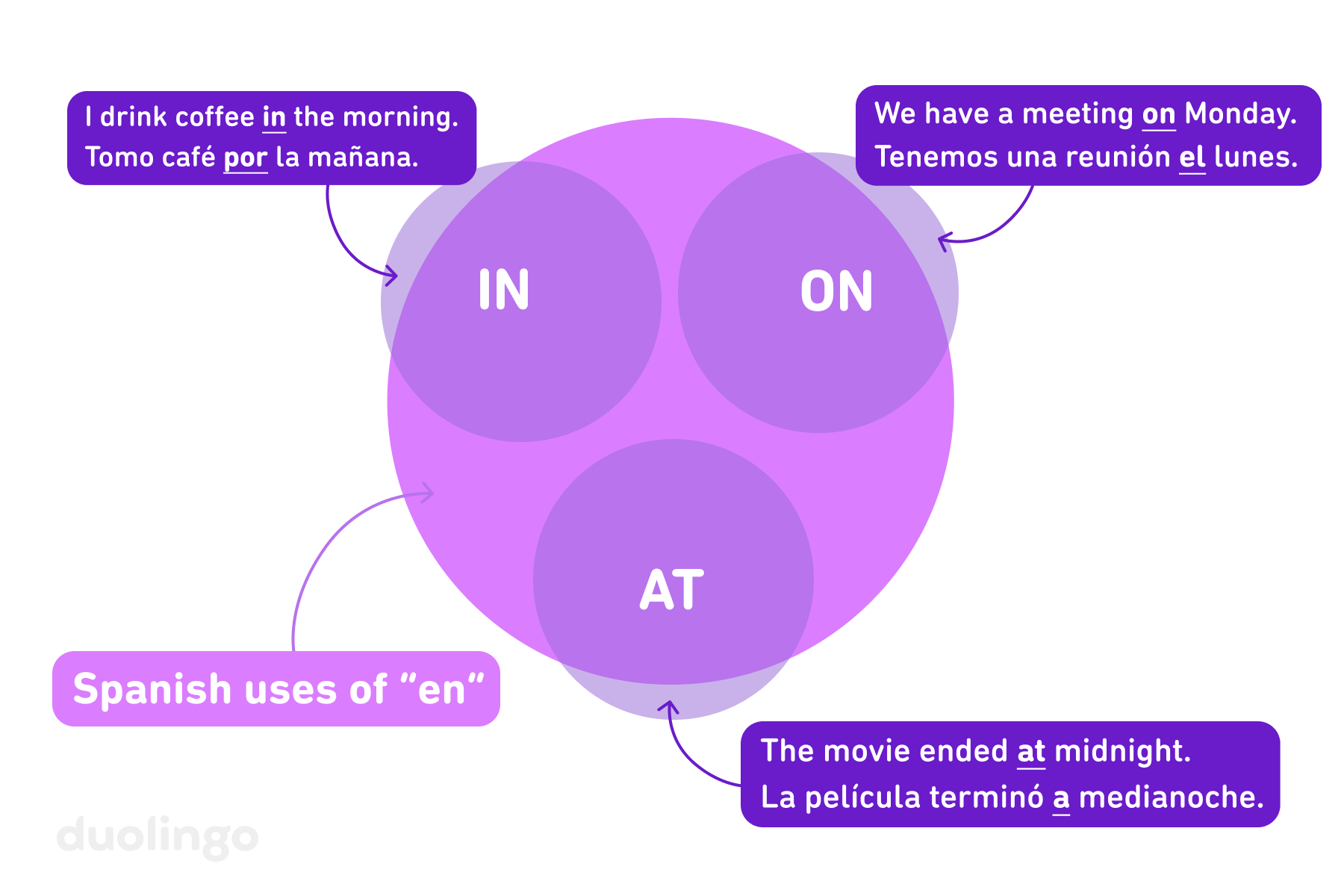

In a given language, a preposition can be thought of as representing some core meaning. Here are a few core meanings from English:

- in: location within or into an enclosed space, as in The keys are in the drawer (inside an enclosed area) and He is in love (enclosed in an emotional state)

- on: surface contact and support, as in The book is on the table (touching a horizontal surface) and The show is on TV (a medium as a metaphorical surface)

- at: specific point within a context, as in We met at the park (a specific place) and I woke up at midnight (a specific point in time)

English distinguishes these three kinds of physical and metaphorical relationships—one captured by in, another by on, and another by at—but this won’t always be the same across languages. Where one core meaning ends and another begins isn’t a universal truth or an objective assessment. For example, in most cases, the Spanish preposition en covers all three of these core meanings and can instead be thought of as “location or movement in relation to a reference point.” It captures much of the meanings of in, on, *and* at!

Prepositions across languages

If you’ve studied multiple languages, you know there will be language differences where you least expect them. You might assume that something as basic as saying I’m going to the park vs. I’m at the park would follow the same pattern across languages—but that’s not the case at all, even in closely related languages!

For example, Spanish and Portuguese can use different prepositions for movement toward a place vs. being in a place, while two other Romance languages, French and Italian, each use the same preposition (au in French and al in Italian). Here’s how some Indo-European languages treat these situations as the same or different:

| Language | English to | English at | Same or different? |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | I’m going to the park. | I’m at the park. | different |

| German | Ich gehe zum Park. | Ich bin im Park. | different |

| French | Je vais au parc. | Je suis au parc. | same |

| Italian | Vado al parco. | Sono al parco. | same |

| Spanish | Voy al parque. | Estoy en el parque. | different |

| Portuguese | Eu vou para o parque. | Eu estou no parque. | different |

| Greek | Πηγαίνω στο πάρκο. Pigaino sto parko. |

Είμαι στο πάρκο. Eimai sto parko. |

same |

(Sometimes, different prepositions are possible, but here you just see one option for simplicity).

You can see the situation this puts learners in: If your language uses the same preposition in both contexts, you’ll be surprised to have two different ones in the new language! And if your language uses two different prepositions, it’s easy to forget which one to use in the new language. 😵💫

Languages without prepositions

Another even more mind-blowing fact is that not all languages even have prepositions.

While English and many other languages rely on prepositions to express relationships with space, time, movement, etc., languages can use other tools, some entirely different, the most common of which are cases, postpositions (instead of prepositions) and particles. Even languages that do have prepositions (like German) often use them together with other grammatical strategies (like cases).

Case systems

Languages like German, Russian, Finnish, Turkish, and Basque use case systems to add information directly to nouns (and other words), often reducing the need for a separate word (like a preposition).

For example, Turkish uses an ending on a noun to show location—sort of how we use in in English. One version of this ending is ‑ta, and it is added to a noun, like mutfak (kitchen), to create a single word with the location information: mutfakta (in the kitchen). You can replace ‑ta with different case endings to express other meanings, like ‑tan to show source or starting point, as in mutfaktan (from the kitchen).

Sometimes, a language can even combine an actual preposition with different case endings to express different meanings! German has a set of such prepositions, including in and an (two German prepositions, that happen to look like English!). When followed by one case, they indicate movement, but when followed by another, they show location:

| Preposition | Accusative case (for movement) | Dative case (for location) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| in | German | Ich gehe in die Schule. | Ich bin in der Schule. |

| Translation | I’m going into the school. | I’m at school / in the school. | |

| an | German | Ich hänge das Bild an die Wand. | Das Bild hängt an der Wand. |

| Translation | I’m hanging the picture on the wall. | The picture is hanging on the wall. | |

Here, die is the accusative form of the (feminine) definite article, so it gives in and an a meaning related to movement, whereas der is the dative form of the same article, so it gives in and an a meaning related to location without mention of movement.

Postpositions

Did you ever notice that prepositions go before a noun? But they don’t have to! Instead, some languages place these words after a noun. For example, to say before class in Basque, you can say klase aurretik, and in Turkish dersten önce. In both cases, the noun comes first, so you’re literally saying class before!

Particles

Japanese and Korean use particles that function differently from prepositions and postpositions, but serve a similar role. For example, in Korean, to say on the table, you’d say 식탁 위에 (siktak wie), where 식탁 (siktak) means table, 위 (wi) is a noun that expresses the meaning on, and 에 (e) is a locative particle—a word that shows location. It’s essential to the grammar and has to occur with 위 (wi).

The Japanese for on the table is テーブルの上に (tēburu no ue ni), where テーブル (tēburu) means table, の (no) is a particle that links nouns together (here, table and top), 上 (ue) means top, and に (ni) is the location particle that indicates that we’re talking about something that’s happening on top of the table (as opposed to just saying the top of the table).

Here are some examples of these non-preposition strategies for location and movement towards a place:

| Language | English to | English at | Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | I’m going to the park. | I’m at the park. | prepositions |

| Basque | Parkera noa. park-to I’m-going |

Parkean nago. park-in I-am |

case system |

| Turkish | Parka gidiyorum. park-to I-go |

Parktayım. park-in-I am |

case system |

| Korean | 공원에 가고 있어요. Gongwone gago isseoyo. park-LOCATION I’m going |

공원에 있어요. Gongwone isseoyo. park-LOCATION I-am |

postpositioned particle |

Access new ways of thinking!

When you learn how to use prepositions (or their alternatives) in a new language, you change how you think about space, time, and relationships. Keep going—you’re not just learning grammar, you’re expanding your mind!

For more answers to your language and learning questions, get in touch with us by emailing dearduolingo@duolingo.com.