In this week’s Dear Duolingo, a learner asked about "oral" versus "written" languages and how languages get new writing systems. You can read about the differences between a language and how it's written in the post, but that's only the tip of the iceberg! In fact, many languages are undergoing this process today and are being written down by their communities for the first time—or for the first time with their input.

To learn more, I talked to Dr. Hilaria Cruz, an Assistant Professor of Comparative Humanities at the University of Louisville. Dr. Cruz is a Chatino speaker from near Oaxaca in Mexico, near some of the Mixteco-speaking communities that our Dear Duolingo reader wrote in about. Chatino was largely undocumented—and unwritten—until the last century or so, but today, Dr. Cruz writes children's books in the language. Here's the story of how the Chatino writing system developed.

Chatino and indigenous languages in Mexico

Today, there are hundreds of indigenous languages and dialects of those languages spoken throughout Mexico. Chatino and Mixteco are two of the languages spoken in and around the Oaxaca region. They are very (very!) distantly related, sort of like Spanish and Norwegian, and are part of a huge language family called Otomanguean. Today, they might not have much in common linguistically, but they do share a story of colonization and discrimination.

“Literacy is one of the tools that western nation states have used to do away with indigenous languages,” Dr. Cruz explained. “It continues to be used to exterminate indigenous languages.”

In the case of Chatino, most of its linguistic documentation happened only in the last century, and for very specific uses. According to Dr. Cruz, “nation states did not want to fund any research on the native languages in Mexico. Most of the work done in these languages was translating the Bible, from the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) group, until the 2000s!”

The result was a writing system developed by the English-speaking missionaries and based on Spanish. But of course, Chatino is totally unlike Spanish, and there were lots of written representations that Chatinos like Dr. Cruz were reluctant to use. “Chatino has laminal sounds, glottal stops, nasal sounds,” Dr. Cruz said. “But how do you represent these different sounds that don't exist in Spanish?”

A new writing system for Chatino

One of the biggest challenges was representing tones. Like Chinese, Chatino is a tone language, and while Chinese has 4-5 tones, Chatino has more than 14.

Dr. Cruz recalled that the community “didn't have a lot of models of how to account for the tones. SIL used numbers to represent them, but people in the communities didn't like that.” So how did they do it?

“We decided to represent [the tones] with letters of the alphabet. We took examples from Hmong! Our system is really nice because it was designed to capture the phonological tones of the 17 Chatino languages. It recognizes the diversity of Chatino varieties.”

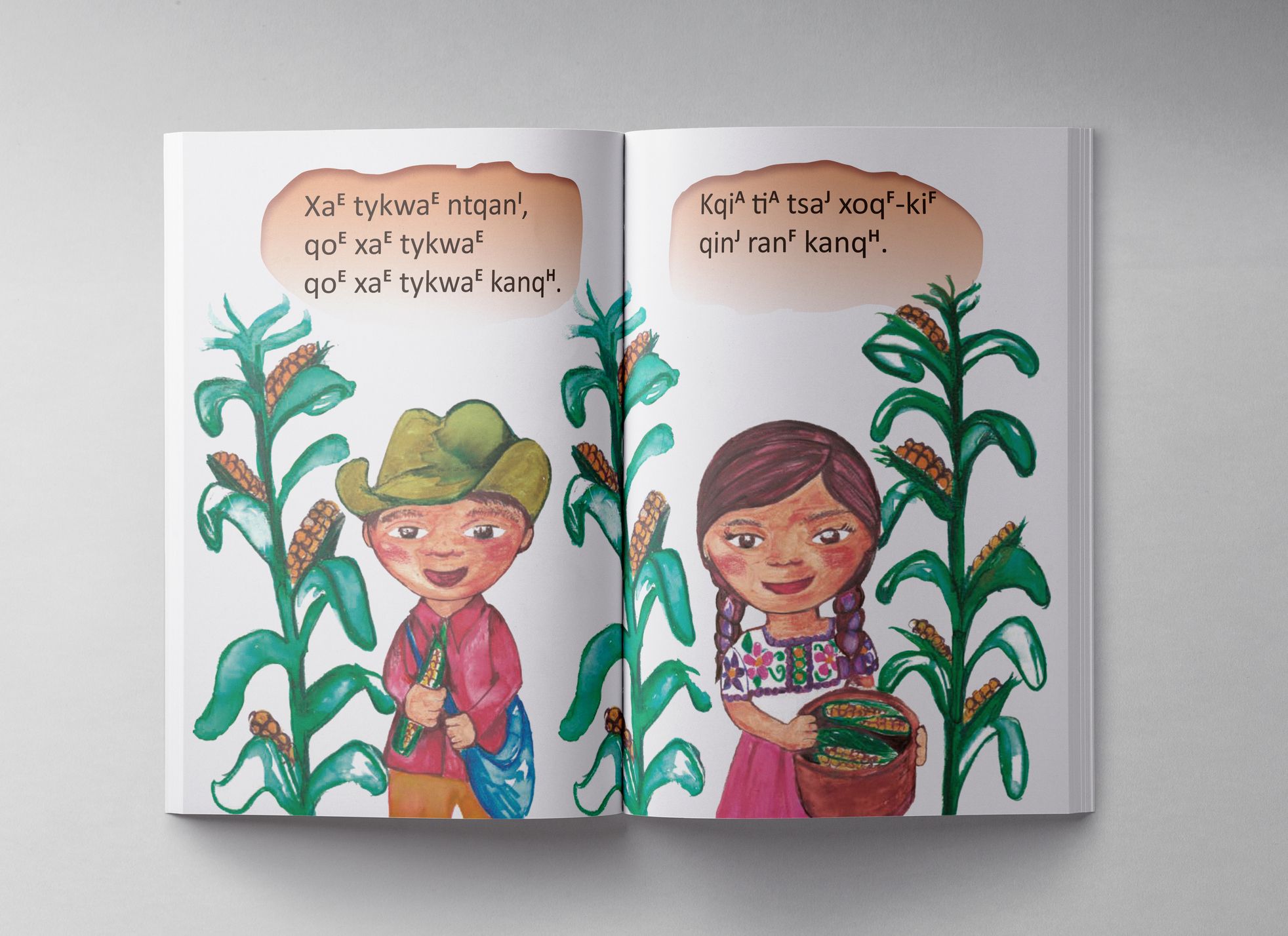

These tone letters are written as superscripts, small, capital letters raised at the end of a syllable.

The work of Dr. Cruz and linguists from the Chatino communities has created a writing system that matches the intuitions and needs of Chatino speakers. But developing a common standard is only part of the problem.

Getting the new system into the community's hands

“Schools right now are still forcing children to acquire these dominant languages [like Spanish],” Dr. Cruz said. “Companies, too—by not acknowledging these languages.”

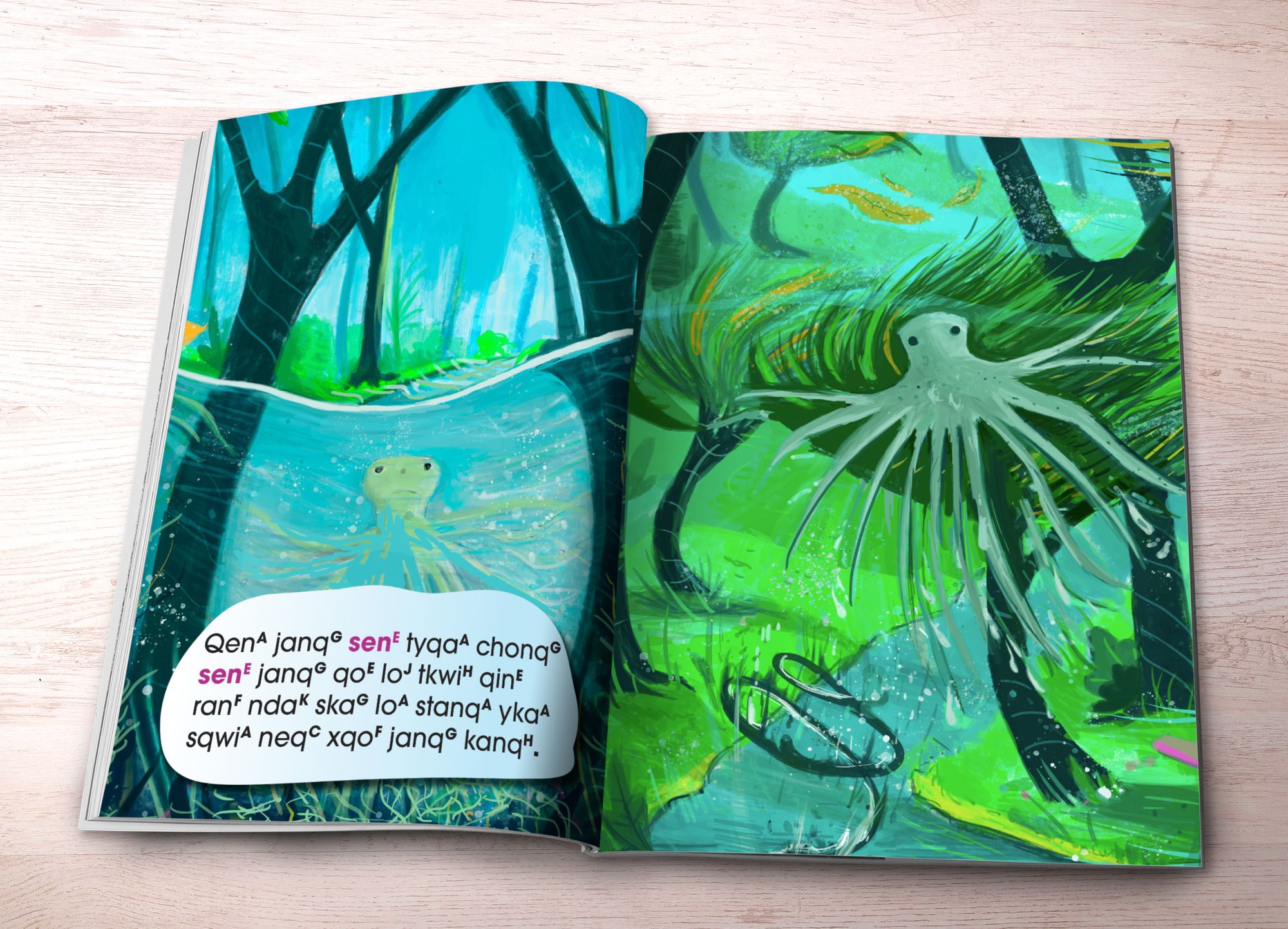

Recently, Dr. Cruz has written children's books in Chatino to encourage literacy and linguistic pride among Chatinos—but it hasn't been easy to get the books into the hands of Chatino children.

“In Mexico, the language of instruction still continues to be Spanish,” explained Dr. Cruz. “We've worked outside the school system, and we have a growing number of Chatino speakers who know how to read and write in this system. But Amazon has refused to publish these books because these languages are not in their systems. And what languages are in their system? European languages.”

The stories in Dr. Cruz's books revolve around different groups of Chatino tones, sort of like how rhyming books in English play with sounds so kids (and grown ups!) can have fun with language. In the image above, many of the words on the left page have the “E” superscript, showing they are all from the same tone class.

“When you play with the tones, it's very easy for the children to learn it,” Dr. Cruz added. “When I brought the first book to the community, the kids picked it up right away! It made it really easy for them.”

There's something else that sets these Chatino-language books apart from other options for kids in Oaxaca.

“There is no translation into a major language,” Dr. Cruz pointed out. “Most of the reading materials coming up in native languages are bilingual, with the native language and a major language [like Spanish]. But my intuition is that when you are presented with a book that is bilingual, with an orthography you don't know, it's very natural to gravitate towards the writing system you do know.” That can often leave Chatino and other native Mexican languages behind, if it's next to a more familiar writing, like from Spanish. “The other writing is seen as decorative and then you move on.”

Community is key to a new writing system!

The way a community writes their language represents how they understand their language and culture—and it probably says a lot about their history and external influences, too. That's been the case for Chatino, Haitian Creole, and Korean, among many others.

You can read Dr. Cruz's books in Chatino for free at ThinkIR at the University of Louisville and Dartmouth Digital Commons, and Dr. Cruz supports her project via a GoFundMe fundraiser.