Welcome to another week of Dear Duolingo, an advice column just for learners. Catch up on past installments here.

Hi learners! This week's question is all about accents—but with an interesting spin that will be especially relevant to those of you who regularly use a second language. Let's take a look!

Our question this week:

This question has interesting science behind it—more on that below!—and it came up recently at work. My colleague Gabriela Talarico is from Brazil, and she's a professional translator: Her English is excellent. She pointed out that some native English speakers struggle to understand her more than other people who speak English as a second language. That can seem counterintuitive… but it makes a lot of sense when you dig into it!

Accents are odd: They are as much about how we hear as about how we pronounce things. Our first language (and the first accent we learn!) sets the standard for how we hear language sounds, including sounds in a new language we're learning and the sounds we hear in our own language (including from non-native speakers).

Then our brains have to match what we hear to what our brain is expecting—and that's where things get really interesting!

Accents in our brains

We've discussed how sounds work, and why they are so difficult to learn, elsewhere, but here are the most important points:

- Sounds are categories. Any sound is actually a whole range of sounds that our brain groups together! For example, there isn't a single, exact way to pronounce a "t" sound (in English, Spanish, or any language!)—instead, your brain lumps many acoustically different sounds into the category "t." The same is true for vowels and other kinds of consonants.

- Sounds are super variable. The way you pronounce "t" (even in your own language!) is slightly different every time: It's influenced by how quickly you are speaking, what sounds you pronounce before the "t," what sound comes after, the word itself, and lots more!

Match Madness… for accents!

Your brain learns the particular categories of not just your language (like English), but your specific dialect and accent (like Pittsburgh English). That's why you can hear another accent of your own language and almost feel your brain go, "Wait… was that a 't' sound?!" It can take extra split seconds for your brain to map an accented word or sound to the categories it has stored in your brain. Your brain is doing a complicated matching task!

Part of what makes this auditory matching task difficult is the distance between your own sound categories and the sound categories of other people. For many sounds, you really can think of the categories as being physically distant—although the distances are extremely tiny inside your mouth 😅

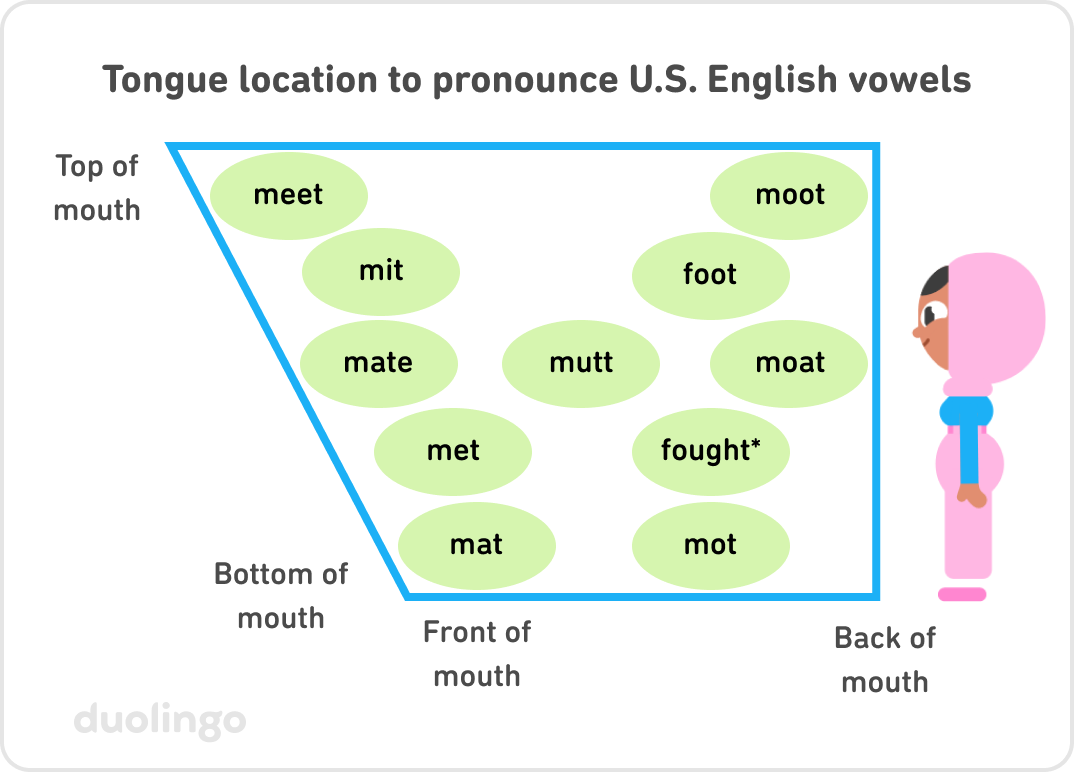

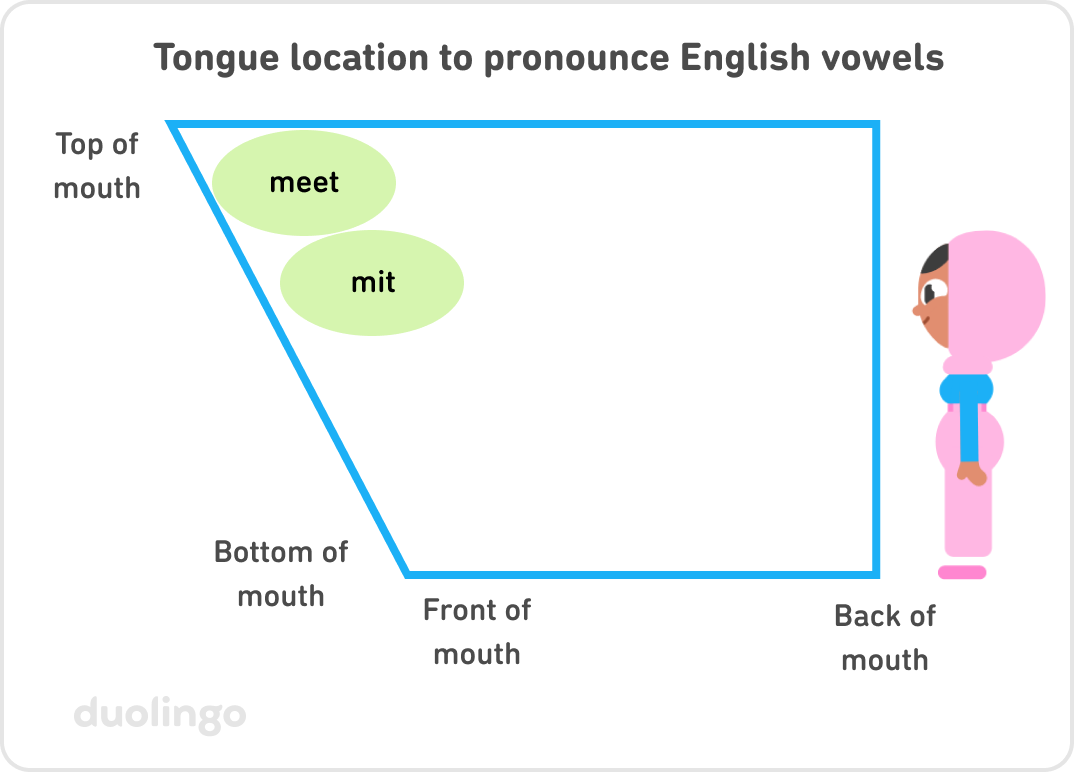

Let's use English vowels as an example: Your tongue has to jump around to different parts of your mouth to produce vowel sounds. You can think of your mouth like a tiny grid with different vowel coordinates:

Imagine you're facing the same direction as Zari, so that the left side of the diagram is the front of your mouth and the right side is the back of your mouth. (This diagram only shows 2 English vowels—the ones in meet and mit—but actually there are tons of vowel categories crammed in there! Check the end of the post for the diagram for U.S. English.)

To make the vowel sound in meet (which is /i/ in the International Phonetic Alphabet), your tongue has to move to the very top and front of your mouth—and you can see from the size and shape of the green meet bubble that there are a number of different coordinates that English speakers count as this "ee" sound. The English "ee" coordinates neighbor the English "ih" coordinates, as in mit (/ɪ/). But everyone's coordinates are slightly different, even for the same "accent"... and different accents can have very different coordinates!

Then, of course, there are other languages 👀 They can have both different vowels entirely and different coordinates for vowels that seem the same 🤯 So the matching task really does turn into madness: Some languages will have more vowels than your language (creating certain challenges for listening), and others will have fewer vowels than your language (that's a whole other set of challenges).

For example, Spanish doesn't have the mit (/ɪ/) vowel sound at all, and the Spanish meet (/i/) category is a bit bigger than the English one—which means Spanish speakers have to learn new coordinates for mit *and* English speakers listening to Spanish-accented English might hear sounds like the meet category that are meant to be words like mit.

How our brain learns new accents

But your brain is really resourceful in how it figures out what to map to which category. Here are just a few factors it takes into account:

- Based on context, what the word must be. For example, your brain might guess a word you heard is tooth and not dooth... since dooth isn't a word in English.

- What else it knows about the accent. Once it has figured out tooth (vs. dooth), your brain can extend details of the pronunciation of "t" to other sounds, especially "p" and "k" (which typically pattern together).

- Other experiences with the accent. Even if you're listening to a new person, it might not be an entirely new accent for you and your brain. Your brain might have some memories about how to shift sound categories to do the mapping!

And for those of us using a second language, there is often an additional factor: consistency. We're so practiced at our first language, that our categories (tongue coordinates!) are pretty consistent: When I say words with the meet vowel, my tongue is basically always in that green bubble. But for vowels that are newer to me, even in languages I'm pretty proficient in, my categories are likely to be broader in general and also less like the categories of a native speaker.

But language proficiency isn't the only factor at play: Our brains, tongue, and mouth are also sensitive to frequency—to what we've been hearing or producing most recently. That's why people often report that they "go back to" the dialect and accent they grew up with after being home for a while, or that it takes them a while to "adjust" to using one of their languages after a long hiatus.

And that's what my translator pal Gabriela and her friends noticed: Often, non-native speakers are quite accustomed to listening to other non-native speakers, and sometimes more so than native speakers. If you're a native English speaker who doesn't have much experience with foreign accents (or even regional accents!), your brain's categories might not shift quite as easily to do the matching task. Or if you are very accustomed to hearing Portuguese-accented English but don't hear much Hungarian-accented English, you might be quick to match Portuguese accents to your own sound categories, but are slower or less accurate when matching them to Hungarian accents.

Accents are in the brain of the beholder!

How we hear accents has a lot to do with our brain and our experiences—and our sound categories can be changed both intentionally and totally by accident. What other accent questions do you have? Let us know by emailing dearduolingo@duolingo.com!

U.S. English vowel diagram

These are the general coordinates of the U.S. English vowel categories. Note that not all dialects have the vowel represented by fought—it's most common in the northeastern U.S.